Maba-ay 2.0: Igorot Hunter, DC & Marvel Heroes, and Local Entrepreneurs

CULTUREINDIGENOUS PEOPLESIGOROTS

Scott Magkachi Saboy

5/2/20244 min read

The Tarnate-Bernardez compound in Maba-ay, Bauko, Mt. Province is one of the more interesting stopovers along the Halsema Highway, around 100 kilometers NNE of the Philippines’ summer capital, Baguio City.

At the center of the area is a refueling station, Caltex Maba-ay, flanked by a vegetable-and-fruit stand to the right and the Mountain View Café to the left, and walled at the rear by the residence/business office of the proprietors. A store at the entrance of the café offers various delicacies from breads and pastries to balut and siomai. Inside the café, one is treated to a display of “native” wooden fixtures and a lovely view of the misty mountains made verdant by pine stands and vegetable patches. Behind the café, one goes down to a yard where a dilapidated Mountain View Liner bus is parked.

Igorot businesswoman Juran Tarnate-Bernardez runs the gas station which her parents established in 1982 and which was originally located a short distance down the road. She relocated the business to the new site in 1997. Her husband, Gilbert “Bobby” Bernardez, a Kankana-ey Igorot, put up the café in 2012.

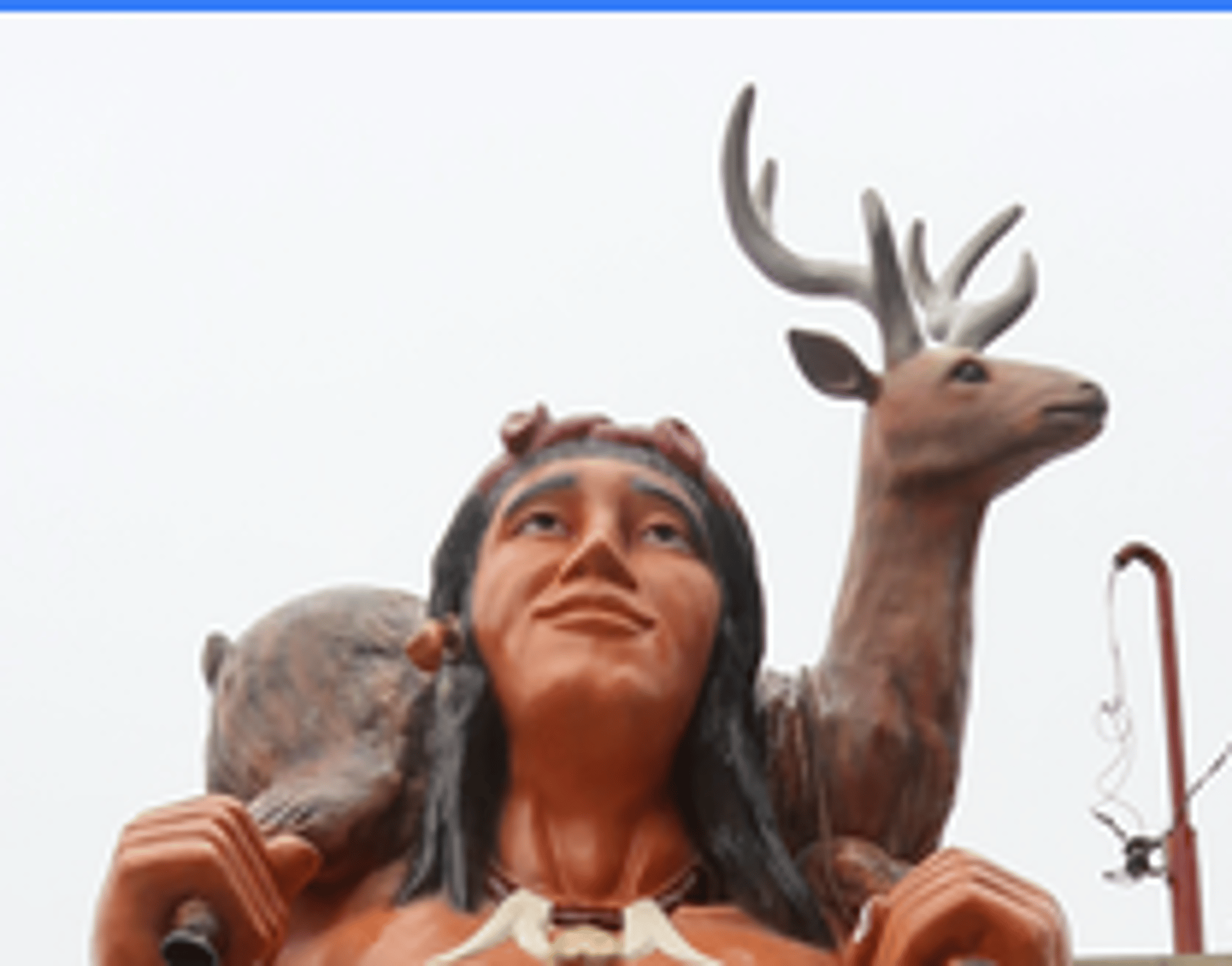

The first thing about the place that strikes the viewer is the 22-foot statue of a pastel-colored Igorot hunter with a deer slung across his shoulders and a black hunting dog at his feet. The three figures cast an idyllic impression, especially with the careful placement of visual directions: the dog gamely looks upward to its master and the prey, the hunter softly looks ahead of him, and the deer calmly gazes towards the left. It may seem like a romanticized take on local culture, but as I briefly illustrate below, when read within its spatial context it actually casts on the observer a sense of ethnic pride through the creative reconfiguring of a global fad into a local symbol.

But to continue, visitors can also readily notice one DC and two Marvel heroes poised according to their characters: The Hulk plants his 12-foot frame in a menacing pose between the restroom and the fresh goods shop (perhaps pissed that instead of starring in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, he is now guarding a toilet in a mountain town far, far away; or mad that being set alongside stacks of chayote, wombok, and pipino has made him look like a genetically modified rootcrop); Spider-Man is on the alert crouching at the left side of the sari-sari store as if to say to the gigantic Igorot, “I got your back apo lakay!”; and Batman knuckles up inside the café as he stands in a corner facing the entrance and sending his strongest UHF message ever: “Corona alert: Bat-eating comes with great responsibility.” Both Spider-man and Batman are around six feet tall.

The statues all came from Sison, Pangasinan. The Igorot figure, claimed by the Bernardez couple as the first of its kind in the Cordillera with a twin somewhere in Cagayan, was made by an artist named Joel Buyagao. The Hulk used to be in the same spot but was kicked out and consigned near the restroom when the monolithic Igorot came (perhaps another reason why the green Avenger was livid when I took his photo).

Evident in my short conversation with the proprietors is their rootedness in their traditional culture while being engaged in contemporary capitalistic ventures. For Juran and Bobby, making the Igorot hunter the centerpiece of their displays in the whole business enterprise is just a simple representation of their ethnicity.

I would say though that they have provided us a far more complex signifier to consider. Imagine an FBI (Full-Blooded Igorot)-DC-Marvel alliance with the local culture hero Lumawig leading the charge. How iconic it is to depict an Igorot warrior-lord towering over the landscape with some of the greatest superheroes of Western pop culture as his diminutive sidekicks. Call it the Rise of the Indigene. In this postcolonial era, the world is turning to indigenous knowledge systems and practices for insights into how the devastating effects of climate change can be mitigated; in the academe, Indigenous Studies has foregrounded a research paradigm that effectively counters dominant White/West-centric discourses (see Linda Tuhiwai-Smith’s Decolonizing Methodology, Eva Garroute’s Real Indians, among others). Cordillerans, too, continue to make their own narratives heard in international groups like the Igorot Global Organization (IGO), or in fora like the International Conference on Cordillera Studies (ICSS). Igorots have also risen to prominence in the international geopolitical arena — e.g., Victoria Tauli-Corpuz (UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), or Joji Cariño (former director of the UK-based Forest Peoples Programme).

The 89-year evolution of the 150-kilometer “Mountain Trail” into “Halsema Highway” narrates a fascinating journey of rugged indigenous cultures forever changed by the twin juggernaut of modernity and colonization. Just as the now-defunct Mountain View Liner has been commercially reconfigured into a cafe, this mountain thoroughfare — listed as among the world’s “25 Most Dangerous Roads” — continues to be historically and culturally reconfigured largely by enterprising natives who have constructed their own markers that tell multiple stories of luck, ingenuity, persistence, and sacrifice. It has also been honored by internationally known Igorot influencers who had/have regularly taken the Baguio-Bauko/Bontoc/Besao route and know the road’s markers, twists and turns by heart.

The Bernardez couple have ventured into a viable business which they can pass on to their children. I’m sure they will eventually realize too that in so doing they have actually unfolded an inspiring story that somehow mirrors the history of their ili (community) and luta (land).